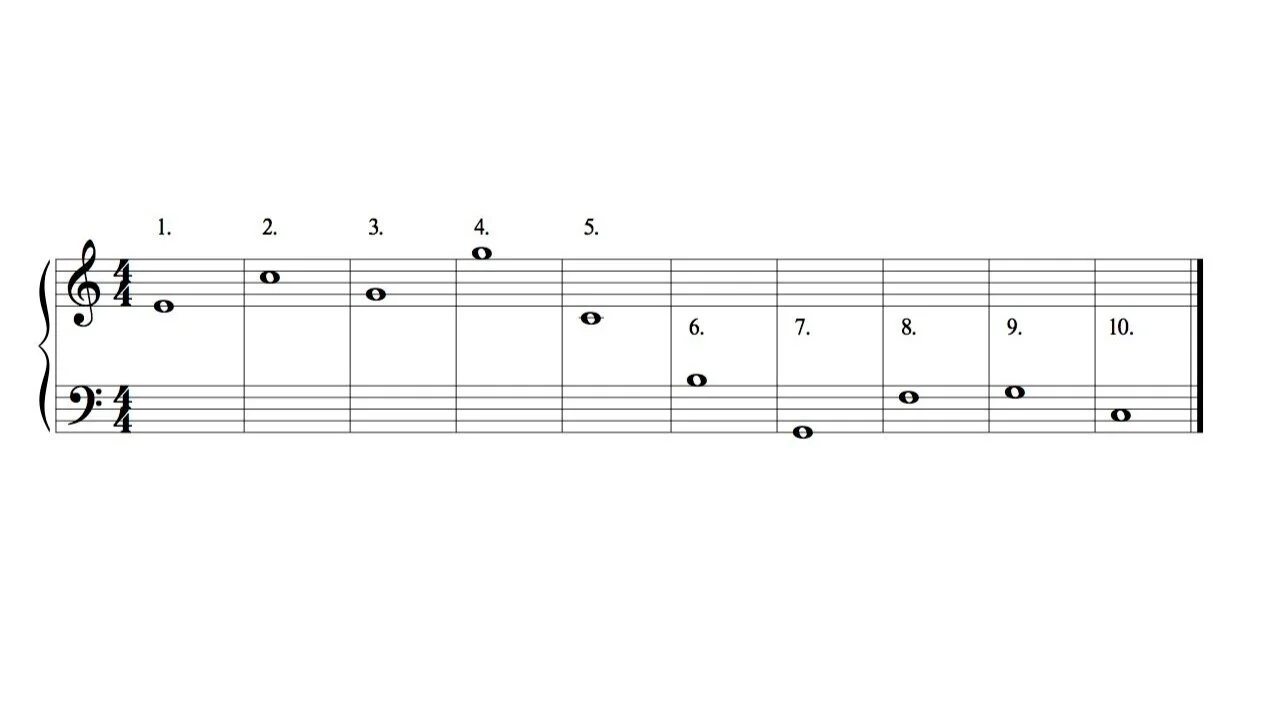

ESSENTIAL 2: Traditional notation OF PITCH

QUIZ: Traditional pitch notation

After watching the video, take this quiz to celebrate your mastery!

Traditional Notation of Rhythm

QUIZ: Traditional Rhythm notation

After conquering the vid, conquer the Tenuto Challenge! (pitch only)

https://www.musictheory.net/exercises/note/brwyrybynyydeb

TRADITIONAL MELODIC NOTATION (PITCH, CLEF)

In this lesson, we are going to explore the musical notation of pitch.

Notation is a written way of recalling or communicating how a tune goes. So the goal of pitch notation is converting pitches into writing and back again.

Perhaps you already know that this is a Grand Staff, and you know what pitches are represented by each line and space on the staff. But you might be interested in the fascinating back story to how we got to this system, and will therefore have an appreciation for the next notational system that will, no doubt, replace this one in your lifetime.

You know, every melody has ups and downs—a contour of the pitches. Let’s imagine that you just created or heard this melody, and you want to remember it. “A Mighty Fortress is Our God”

Probably most of us have made these kinds of instinctive marks on a lyric sheet or chord chart, to remind ourselves of when it goes up and down, or it repeats. It might be enough to recall, Oh, yeah, that’s where it moves.

So maybe it is not surprising to see that many hundreds of years ago, Medieval monks did the same thing in their prayer books. They invented various systems to represent the hand signals that the leader would use in keeping them singing together.

The exact pitch is not shown, but the general direction of up and down, and the distinction between a step and a leap, is all implied in the mark.

Then the monks who were literate enough to need such things developed just a bit more accuracy by drawing one straight line above the line of lyrics they were singing. With just one line, you can accurately identify five pitches. Centered on the line, touching above or below the line, and with a space between the line and your neume. The notes themselves were squares or rectangles, for the most part, because that’s what flat quills can draw most accurately.

But our melody here covers more than five pitches. So, after some experiments along the way, the monks settled on using four lines, one for every other step. Now you can identify an octave and a half, which is enough to notate two part harmony. The pitch for middle C was marked on the staff with a small letter C on the second line from the top. (remember, all of the singers were men at that time in the church, so this lower range was perfectly appropriate).

Now we can write the tune to Joy to the World, starting on a C and descending down to C below.

Or we can write out A Mighty Fortress is Our God. In fact, back in the early 1500s, this was actually the kind of staff that was in use at the time. In fact, here is an original notation of the music back then.

So, now, modern notation. Five lines, not 1 or 2 or 4. You make an oval where the pitch is—through a line, or self-contained in the space between lines, touching both. All you have to do is to standardize what the lines mean, and you are golden.

Here’s the secret code: G clef. F clef. Middle C. From there, it unfolds pretty quickly. EGBDF and FACE, GBDFA and ACEG. Leger lines allow you to extend beyond the limits of the staff itself.

The only other thing to add at this point is accidentals: sharps and flats. You can add an accidental before the pitch itself—that’s why they call it an accidental—or you can put it in the key signature at the beginning of each staff. The order in which they are added is predictable and strict, so you have to memorize this, too. But we don’t have to know that yet.

Now, before moving on to the next video, take this quiz to demonstrate your understanding of the terms and concepts.

TRADITIONAL RHYTHMIC NOTATION (RHYTHM, METER)

We have covered the musical notation of PITCH. In this video, we cover the notation of RHYTHM.

At its simplest, notation of rhythm is simply representing whether a note is long or short . Back in the day (a thousand year or so), that was pretty much all they needed for Gregorian Chant. And the same is true for simple folk songs today. For example, “Mary Had a Little Lamb” has regular beats and long notes. SSSSSSLSSLSSLSSSSSSSSSSSSL. Can you feel the difference? Most of the notes are simple short syllables, and sometimes a long one comes a-long one comes a-long one comes along, so to speak. So regardless of whether the pitch goes up or down, the rhythmic values are independent and simple. So we come up with two markings. Maybe a dot and a dash. Dot looks shorter. We used numbers to represent pitch class (remember the 3212333), but we can use dots and dashes or something to represent length. A dot after the number means that it is a regular short length, and a dash attached to the number means it is twice as long.

Short-long. “Mary Had a Little Lamb.” ……-..-..-

That’s a pretty serviceable system. If only all music were as simple.

Short-long-longer. “A Mighty Fortress” .--..-..-------..-x

Shorter-short-long-longer. “Come Thou Fount (Teach me some melodious sonnet) -..xx----x-..xx—x=x

There are usually no more than 4 levels of rhythmic length to musical pitches in a song. If “short” is the value of 1, then the other values are ½, 2 and 4. If those are the only values we needed, I think we’d be okay, once we learn a system and get used to it. But sooner or later, we need more than these standard four values.

You might say, “Why not simply write down how long a note lasts? Wouldn’t that answer everything? Start the clock and record when each note turns on and off.

But the math gets really confusing very quickly, and become hard to remember or to realize. Especially considering various TEMPO settings. Pulse is groupings of notes.

MIDI events would solve this. But they are not always clear at a glance.

The other thing that makes it confusing is that besides PULSE or TEMPO, the pitches are sometimes divided into 3 rather than into 2 or 4.

MIDI events still work for this. And I believe they may take over as the next writing system. But not yet. The math works out for triplets to subdivide by 3 instead of even numbers.

“My Country Tis of Thee” ¾ with dotted rhythm

In fact, sometimes the tune itself subdivides into 3.

“Blessed Assurance”

All of these challenges are solved by knowing TWO secret codes of rhythmic notation: TIME SIGNATURE and THE VALUE CODE.

Value code is simple, if you remember this: the more black you add to it, the faster the note.

Start with whole note (longer) = just a circle

Half note (long) = add a stem

Quarter note (short) = fill in the circle

Eighth note (shorter) = add a flag

It’s like a pie, if you like to eat a quarter of a pie at once (saves time). Whole = 4 pieces. Half = 2 pieces. Quarter = 1 piece. Eighth = half a slice. If you think too much about it, all the fractions are dumb. The British system is worse! (quavers and such)

All of that is fine, as long as you have all multiples of 1,2,4,8. But what if you need a 3? You add a dot (2+1=3). That gets you just about everything else you need. Such as 5 (=3+2) or 7 (4+3 or 2+3+2), as long as you can add it on any level.

¾ with dots

“My Country Tis of Thee”

“Star Spangled Banner”

4/4 with dots

“Swanee River”

“Brahms Lullaby”

TIME SIGNATURES

Repeated combinations of pulses. Strong-weak = 2. Strong-weak-weak = 3. =4.

“Jesus Loves Me”

“We Will Rock You”

clap on 2 and 4 (it’s unnatural! It bring balance to the force!)

Pickup notes.

“Amazing Grace”

“All Hail the Power”

“Star Spangled Banner”

And now that you have watched the video, take this quiz to show that you can read and write traditional rhythmic notation.

#2c TRADITIONAL NOTATION

(SCALES, KEY SIGNATURES)

We wrap up the second topic of traditional notation by talking about key signatures and scales in this video.

When we create these major scales that we were talking about in the last video, they come in certain patterns. I had drawn them as building blocks in the last video. But they aren’t, in fact, equal size blocks for each scale degree. Some are bigger than others (whole steps), and others are smaller (half steps). You can see them in a midi events layout (or Legos stack) that a major scale is made up of patterns of whole and half steps. It becomes confusing on a piano keyboard or guitar fretboard, but as far as patterns of whole steps and half steps, it is really quite simple. They all look like this: WWHWWWH. The pattern is easy to remember if you learn it this way: two tetrachords of 4 notes each, disjunct by a whole step. Each tetrachord is in the pattern of WWH. The note, and then step up a whole step, another whole step, and then a half step.

So, a major scale goes in this pattern: WWHWWWH. Seven pitches, covering an octave. Using the white keys on a piano, and starting from C (don’t ask why we start on C; it’s a long story), a major scale is simply following all the white keys. End of story. There were no sharps, no flats, because there were no black keys.

But when I try to play that same pattern starting on an F, for instance, the scale sounds slightly different. Right at this point, the fourth scale degree, it sounded too high, too happy. So we have to lower it, make it flat (as they used to say, “soften” it), use a black key, which is called a B flat. Now it sounds right, but we have to use a Bb every time in order for it to keep sounding right. When we write out the music, we can add a flat every time (they used to call it “musica ficta” or “false music,” because it seemed like a mistake every time). But eventually, it would be good if we simply put a label on the left side and have that count for the entire line. I put a Bb on the left side here, and now the default is not a B but a Bb. We started and ended this scale on F. So we call this key signature (with a Bb) the key of F major. It’s the only major scale that needs exactly one Bb in it to sound right.

Now let’s start on G. One sharp = G.

Circle of fifths/fourths.

Order of sharps and flats.

When we do this with an E, it is even more wild-sounding. That’s because the pattern of W and H has been changed. In order for the E scale to sound right, we have to use several black keys; 4 of them, to be specific. And that means only 3 of the white keys are used for this scale. Four sharps, every time, is the key of E major, and it’s the only one that comes out that way.